SIMON WOHLFAHRT/AFP via Getty Images

- A team at the University of Chicago says they've found a new way to protect art from AI.

- Their program, Glaze, cloaks an image that feeds learning models with inaccurate data.

- Downloaded over 890,000 times, it offers artists a chance to counter AI taking their work without consent.

In the fall of 2022, AI came for Autumn Beverly.

It was only months after the 31-year-old based in Ohio started pursuing art full-time and quit her day job as a dog trainer. She'd tweet her work, mostly colored pencil sketches of animals, trying to make a name for herself. Gigs trickled in — a logo request here, a concept art job there.

At the time, generative artificial intelligence was starting to impress people online. AI would soon be better than human artists, Beverly was told. Her new career was slipping away, but there was little she could do.

Then it got personal. In October, Beverly checked a website, HaveIBeenTrained.com, that reveals if an artwork or photo was used to teach AI models.

Her recent work was just a fraction of what had been harvested. Even drawings she posted years ago on the image-sharing platform DeviantArt were being used to create a bot that could one day replace her.

"I was afraid to even post my art anywhere. I'd tried to spread my art around right before that, to get my art seen, and now that was almost a dangerous thing to do," Beverly told Insider.

Thousands of artists share her dilemma as AI dominates global attention: If they market their work online, they'd be feeding the very machine poised to kill their careers.

Glaze exploits a 'ginormous gap' between how AI and humans understand art

Ben Zhao, a computer science professor at the University of Chicago, says the answer could lie in how AI sees visual information differently from humans.

His team produced a freeware program this year called Glaze, which they say can alter an image in a way that tricks AI learning models while keeping changes minimally visible to the human eye.

Downloaded 893,000 times since its release in March, it re-renders an image with visual noise using the artist's computer.

That image can still be fed to AI learning models, but the data gleaned from it would be inaccurate, Zhao told Insider.

If Beverly altered her art with Glaze, a human would still be able to tell what the piece looks like. But the cloaking would make an AI see distinct features of another style of art, like Jackson Pollock's abstract paintings, Zhao said.

Autumn Beverly

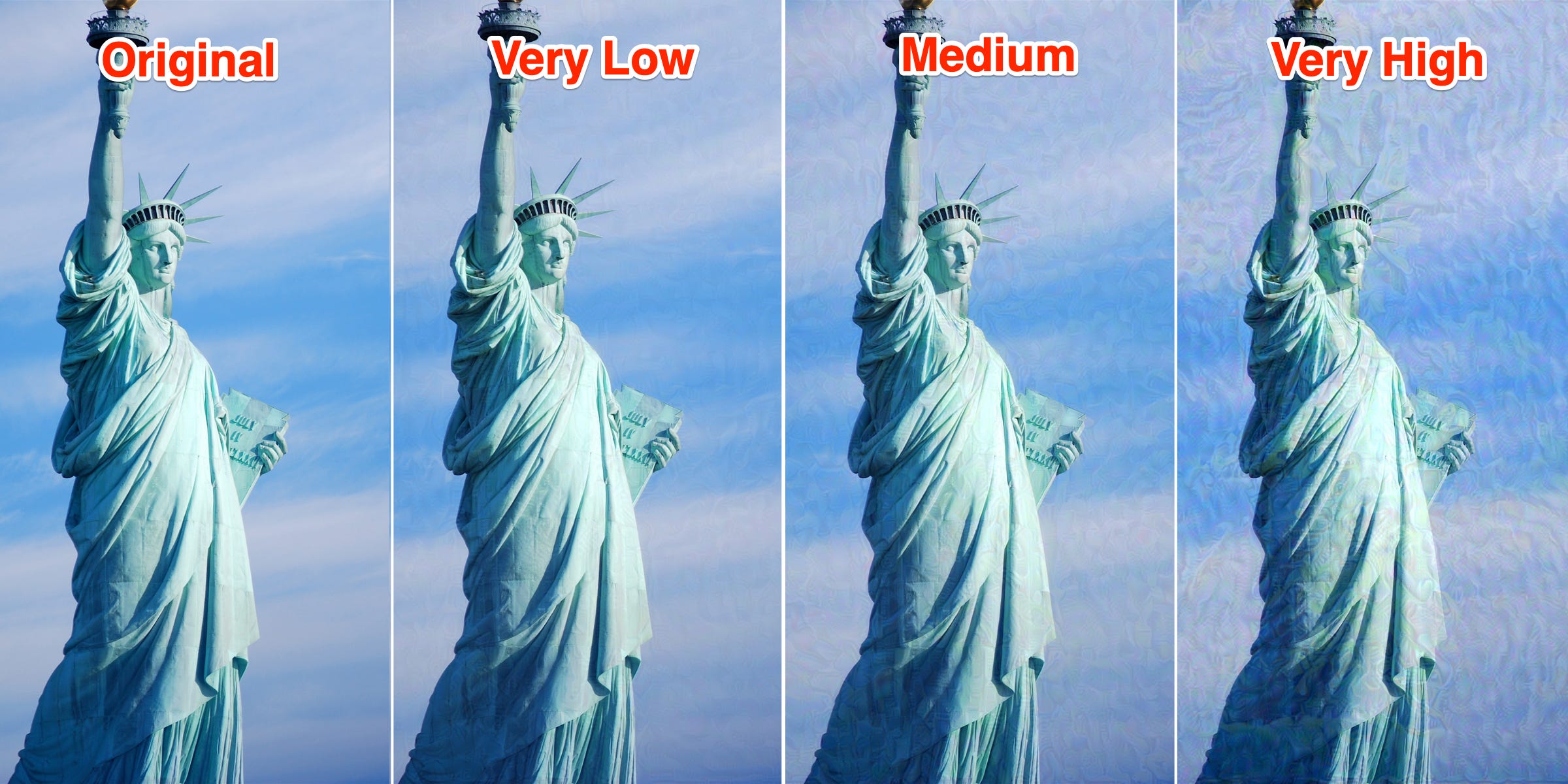

Glaze lets users tweak the intensity of the cloaking, as well as render duration, which could take up to 60 minutes.

Depending on what the user chooses, the visual differences can be stark.

Celso Flores/Flickr

Glaze might look like it's just slightly distorting an image, but the new rendering completely changes how an AI model perceives the photo or artwork, Zhao said.

And it should work across the board with today's learning models, because it exploits a fundamental gap between how AI reads images and how humans see them, Zhao said.

"That ginormous gap has been around for 10 years. People have understood this gap, trying to close it, trying to minimize it. It's proven really robust and resilient, and it's the reason why you can still perform attacks against machine models," he said.

Mixing webcomics with Van Gogh

The main point of Glaze is protecting an artist's individual style, Zhao said. His team conceptualized the program when they were contacted by artists worried that AI models were specifically targeting their personal work.

It's already happening, he added. The University of Chicago team has seen people hawking programs online trained to mimic a single artist's drawings and paintings.

"So someone is downloading a bunch of art from a particular account belonging to a particular artist, training it on these models, and saying: 'This replaces the artist, you can have this if you download it from me and pay me a couple of bucks,'" Zhao said.

Sarah Andersen, who created and runs the webcomic "Sarah's Scribbles," discovered last year that AI text-to-image generators such as Stable Diffusion could create comics in her signature style.

With a following as large as hers — more than 4.3 million people on Instagram — she worries that AI's data on her work could be used as a powerful tool for online impersonation or harassment, she told Insider.

"If you want to harass me, you can type in 'Sarah Andersen character,' think of something really offensive, and it'll spit out four images," Andersen said.

AI-generated/Midjourney

That's where Glaze is naturally positioned to step in, Zhao said. If an AI can't gather accurate data on an artist's style, it can't hope to replace them or copy their work.

In the meantime, Andersen has no way to take down all of her work, which she's consistently uploaded for the last 12 years. Besides, social media contributes to essentially all of her current income, she said.

She's one of the main plaintiffs in a $1 billion class action lawsuit against AI companies like OpenAI and Stability AI, which says the firms trained their models on billions of artworks without the artists' consent.

As legal proceedings continue, Andersen hopes Glaze will serve as a stopgap defensive measure for her.

"Before Glaze, we had no recourse for protecting ourselves against AI. There's some talk of an opt-out option, but when you've been an artist online like me for over a decade, your work is everywhere," she said.

Glaze could kick off an arms race between artists and AI, but that's not the point

Ultimately, if an AI company wanted to circumvent Glaze, they could easily do so, said Haibing Lu, an infoanalytics professor at Santa Clara University who studies AI.

"If I'm an AI company, I actually wouldn't be very concerned about this. Glaze basically adds noise to the art, and if I really wanted to crack their protection systems, it's possible to do that, it's very simple," Lu told Insider.

That could theoretically lead to a pseudo-arms race, where AI companies and the Glaze team continually try to one-up each other. But if AI companies are dedicating resources to cracking Glaze, then it's already partially served its purpose, Zhao said.

"The whole point of security is to raise the bar so high, that someone who is doing something they shouldn't be doing will give up and instead find something cheaper to do," Zhao said.

Tech systems designed to safeguard someone's work are legally protected in some countries, but it's unclear if a program like Glaze might fall under that category, Martin Senftleben, professor of information law at the University of Amsterdam, told Insider.

"Personally, I can imagine that judges will be willing to say that is the case," Senftleben said.

What else can artists hope for?

Artists worried about AI might have few alternatives to Glaze. If creators like Beverly or Andersen want to sue AI companies for copyright infringement, they'd have a tough road to victory, Senftleben said.

"The problem is that mere style imitation is normally not enough for bringing a copyright claim, because concepts, styles, ideas, and so on, remain free under copyright rules," Senftleben said. For example, "Harry Potter" author J.K. Rowling doesn't own a monopoly over stories about a young boy discovering he has magical powers, he added.

One legal course for artists might be a licensing system that pays them when their art is used to teach AI, Senftleben said. Or countries could levy profits from AI-generated works to channel money back into artists' pockets, he added. But it could take years, maybe even a decade, for those laws to take effect, he said.

Glaze aims to fill the gap until those laws or guidelines are firmed up, Zhao said.

"Glaze was never meant to be a perfect thing," he said. "The whole point has been to deal with this threat for artists, where either you lose your income completely, or go out there and know that someone could be replacing you with a model."

Meanwhile, Beverly has started posting her work online again with Glaze, and is one of the platform's advocates. She'd stopped drawing completely from August to October, believing that her career was over, but now is creating and promoting around 10 new pieces a month.

"I think that if there's an ethical way forward, we should definitely push for that. I'm a digital artist. I use updated programs in my work all the time. I'm not against progress," she said. "But I don't like being exploited."

OpenAI and Midjourney did not respond to Insider's requests for comment about Glaze. Stability AI's press team declined to comment on Glaze because it is an unaffiliated third-party software, but said it is implementing opt-out requests in newer versions of its art generator.

LAION, the non-profit that gathers art resources for machine learning, did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Insider about obtaining consent from artists.